In her short life, mathematician Emmy Noether changed the face of physics

On a warm summer evening, a visitor to 1920s Göttingen, Germany, might have heard the hubbub of a party from an apartment on Friedländer Way. A glimpse through the window would reveal a gathering of scholars. The wine would be flowing and the air buzzing with conversations centered on mathematical problems of the day. The eavesdropper might eventually pick up a woman’s laugh cutting through the din: the hostess, Emmy Noether, a creative genius of mathematics.

At a time when women were considered intellectually inferior to men, Noether (pronounced NUR-ter) won the admiration of her male colleagues. She resolved a nagging puzzle in Albert Einstein’s newfound theory of gravity, the general theory of relativity. And in the process, she proved a revolutionary mathematical theorem that changed the way physicists study the universe.

It’s been a century since the July 23, 1918, unveiling of Noether’s famous theorem. Yet its importance persists today. “That theorem has been a guiding star to 20th and 21st century physics,” says theoretical physicist Frank Wilczek of MIT.

Noether was a leading mathematician of her day. In addition to her theorem, now simply called “Noether’s theorem,” she kick-started an entire discipline of mathematics called abstract algebra.

But in her career, Noether couldn’t catch a break. She labored unpaid for years after earning her Ph.D. Although she started working at the University of Göttingen in 1915, she was at first permitted to lecture only as an “assistant” under a male colleague’s name. She didn’t receive a salary until 1923. Ten years later, Noether was forced out of the job by the Nazi-led government: She was Jewish and was suspected of holding leftist political beliefs. Noether’s joyful mathematical soirees were extinguished.

She left for the United States to work at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania. Less than two years later, she died of complications from surgery — before the importance of her theorem was fully recognized. She was 53.

Although most people have never heard of Noether, physicists sing her theorem’s praises. The theorem is “pervasive in everything we do,” says theoretical physicist Ruth Gregory of Durham University in England. Gregory, who has lectured on the importance of Noether’s work, studies gravity, a field in which Noether’s legacy looms large.

Making connections

Noether divined a link between two important concepts in physics: conservation laws and symmetries. A conservation law — conservation of energy, for example — states that a particular quantity must remain constant. No matter how hard we try, energy can’t be created or destroyed. The certainty of energy conservation helps physicists solve many problems, from calculating the speed of a ball rolling down a hill to understanding the processes of nuclear fusion.

Symmetries describe changes that can be made without altering how an object looks or acts. A sphere is perfectly symmetric: Rotate it any direction and it appears the same. Likewise, symmetries pervade the laws of physics: Equations don’t change in different places in time or space.

Noether’s theorem proclaims that every such symmetry has an associated conservation law, and vice versa — for every conservation law, there’s an associated symmetry.

Conservation of energy is tied to the fact that physics is the same today as it was yesterday. Likewise, conservation of momentum, the theorem says, is associated with the fact that physics is the same here as it is anywhere else in the universe. These connections reveal a rhyme and reason behind properties of the universe that seemed arbitrary before that relationship was known.

During the second half of the 20th century, Noether’s theorem became a foundation of the standard model of particle physics, which describes nature on tiny scales and predicted the existence of the Higgs boson, a particle discovered to much fanfare in 2012 (SN: 7/28/12, p. 5). Today, physicists are still formulating new theories that rely on Noether’s work.

When Noether died, Einstein wrote in the New York Times: “Noether was the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began.” It’s a hearty compliment. But Einstein’s praise alluded to Noether’s gender instead of recognizing that she also stood out among her male colleagues. Likewise, several mathematicians who eulogized her remarked on her “heavy build,” and one even commented on her sex life. Even those who admired Noether judged her by different standards than they judged men.

Symmetry leads the way

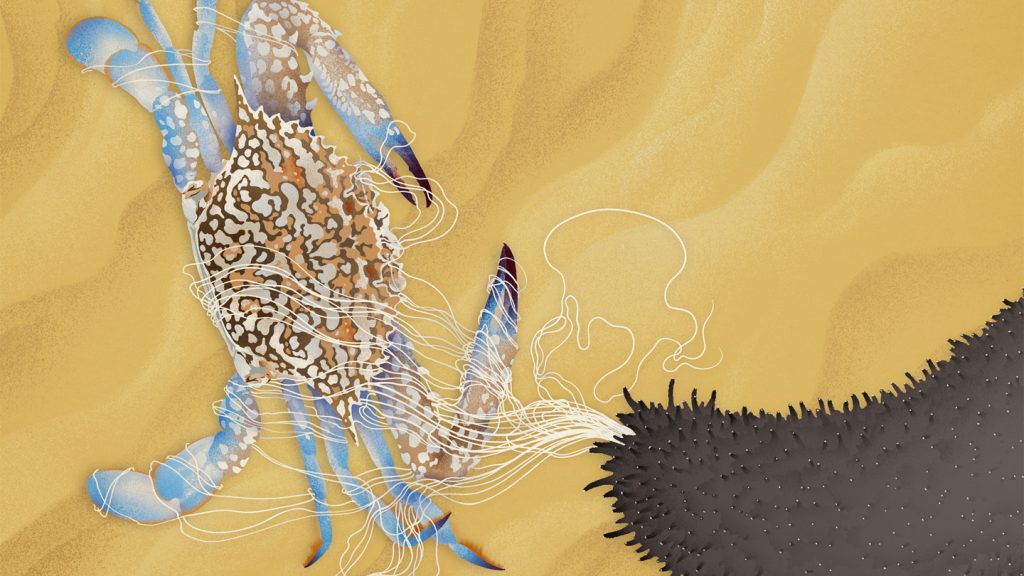

There’s something inherently appealing about symmetry (SN Online: 4/12/07). Some studies report that humans find symmetrical faces more beautiful than asymmetrical ones. The two halves of a face are nearly mirror images of each other, a property known as reflection symmetry. Art often exhibits symmetry, especially mosaics, textiles and stained-glass windows. Nature does, too: A typical snowflake, when rotated by 60 degrees, looks the same. Similar rotational symmetries appear in flowers, spider webs and sea urchins, to name a few.

But Noether’s theorem doesn’t directly apply to these familiar examples. That’s because the symmetries we see and admire around us are discrete; they hold only for certain values, for example, rotation by exactly 60 degrees for a snowflake. The symmetries relevant for Noether’s theorem, on the other hand, are continuous: They hold no matter how far you move in space or time.

One kind of continuous symmetry, known as translation symmetry, means that the laws of physics remain the same as we move about the cosmos.

The conservation laws that relate to each continuous symmetry are basic tools of physics. In physics classes, students are taught that energy is always conserved. When a billiard ball thwacks another, the energy of that first ball’s motion is divvied up. Some goes into the second ball’s motion, some generates sound or heat, and some energy remains with the first ball. But the total amount of energy remains the same — no matter what. Same goes for momentum.

These rules are taught as rote facts, but there’s a mathematical reason behind their existence. Energy conservation, according to Noether, comes from translation symmetry in time. Similarly, momentum conservation is due to translation symmetry in space. And conservation of angular momentum, the property that allows ice skaters to speed up their spins by hugging their arms close to their bodies, emerges from rotational symmetry, the idea that physics stays the same as we spin around in space.

In Einstein’s general theory of relativity, there is no absolute sense of time or space, and conservation laws become more difficult to comprehend. It’s that complexity that brought Noether to the topic in the first place.

Gravity gets Noether’d

In 1915, general relativity was a fascinating new theory. German mathematicians David Hilbert and Felix Klein, both at the University of Göttingen, were immersed in the new theory’s quirks. Hilbert had been competing with Einstein to develop the mathematically complex theory, which describes gravity as the result of matter curving spacetime (SN: 10/17/15, p. 16).

But Hilbert and Klein stumbled on a puzzle. Attempts to use the framework of general relativity to write an equation for conservation of energy resulted in a tautology: Like writing “0 equals 0,” the equation had no physical significance. This situation was a surprise to the pair; no previously accepted theories had energy conservation laws like this. The duo wanted to understand why general relativity had this peculiar feature.

The two recruited Noether, who had expertise in relevant areas of mathematics, to join them in Göttingen and help them solve the riddle.

Noether showed that the seemingly strange type of conservation law was inherent to a certain class of theories known as “generally covariant.” In such theories, the equations associated with the theory hold whether you’re moving steadily or accelerating wildly, because both sides of the theory’s equations change in sync. The result is that generally covariant theories — including general relativity — will always have these nontraditional conservation laws. This discovery is known as Noether’s second theorem.

This is what Noether did best: fitting specific concepts into their broader mathematical context. “She was just able to see what’s right at the heart of what’s going on and to generalize it,” says philosopher of science Katherine Brading of Duke University, who has studied Noether’s theorems.

On her way to proving the second theorem, Noether proved her first theorem, about the connection between symmetries and conservation laws. She presented both results in a July 23, 1918, lecture to the Göttingen Mathematical Society, and in a paper published in Göttinger Nachrichten.

It’s not easy to find quotes of Noether reflecting on the significance of her work. Once she made a discovery, she seemed to move on to the next thing. She referred to her own Ph.D. thesis as “crap,” or “Mist” in her native German. But Noether recognized that she changed mathematics: “My methods are really methods of working and thinking; this is why they have crept in everywhere anonymously,” she wrote to a colleague in 1931.

“Warm like a loaf of bread”

Born in 1882, Noether (her full name was Amalie Emmy Noether) was the daughter of mathematician Max Noether and Ida Amalia Noether. Growing up with three brothers in Erlangen, Germany, young Emmy’s mathematical talent was not obvious. However, she was known to solve puzzles that stumped other children.

At the University of Erlangen, where her father taught, women weren’t officially allowed as students, though they could audit classes with the permission of the professor. When the rule changed in 1904, Emmy Noether was quick to take advantage. She enrolled and earned her Ph.D. in 1907.

As a woman, Noether struggled to find a paid academic position, even after being recruited to the University of Göttingen. Her supporters there argued that her sex was irrelevant. “After all, we are a university and not a bathing establishment,” Hilbert reportedly quipped. But that wasn’t enough to get her a salary.

Although Göttingen finally began paying Noether in 1923, she never became a full-fledged professor. Hermann Weyl, a prominent mathematician at the university, said, “I was ashamed to occupy such a preferred position beside her whom I knew to be my superior as a mathematician in many respects.”

Noether took these knocks in stride. She was beloved for her buoyant personality. Weyl described her demeanor as “warm like a loaf of bread.”

She made a habit of taking long walks in the countryside with her students and colleagues, holding lengthy, math-fueled debates. When legs began to ache, Noether and company would plop down in a meadow and continue chatting. Sometimes she’d take students to her apartment for homemade “pudding à la Noether,” conversing until remnants of the dessert had dried on the dishes, according to a 1970 biography, Emmy Noether 1882–1935, by mathematical historian Auguste Dick.

When she landed at Bryn Mawr, Noether continued her research and taught classes of women — a change of pace from her previous students, who were known as “the Noether boys.” She also lectured at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J. Her death, less than two years after her 1935 arrival, left the academic community grieving.

Russian mathematician Pavel Aleksandrov called Noether “one of the most captivating human beings I have ever known,” and lamented the unfortunate circumstances of her employment. “Emmy Noether’s career was full of paradoxes, and will always stand as an example of shocking stagnancy and inability to overcome prejudice,” he said in 1935 at a meeting of the Moscow Mathematical Society.

Elusive partners

But Noether’s theorems remained relevant, particularly within particle physics. In the minute, enigmatic world of fundamental particles, teasing out what’s going on is difficult. “We have to rely on theoretical insight and concepts of beauty and aesthetics and symmetry to make guesses about how things might work,” Wilczek says. Noether’s theorems are a big help.

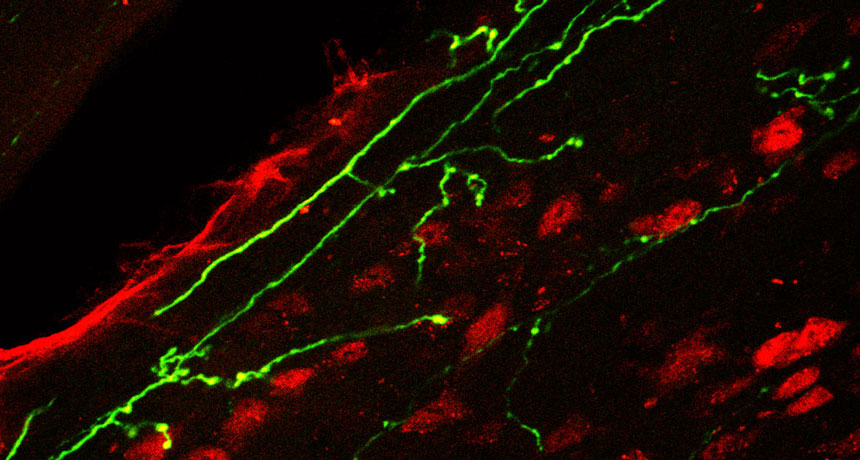

In particle physics, the relevant symmetries are hidden kinds known as gauge symmetries. One such symmetry is found in electromagnetism and results in the conservation of electric charge.

Gauge symmetry appears in the definition of electric voltage. A voltage — between two ends of a battery, for example — is the result of a difference in electric potential. The actual value of the electric potential itself doesn’t matter, only the difference.

This creates a symmetry in electric potential: Its overall value can be changed without affecting the voltage. This property explains why a bird can sit on a single power line without getting electrocuted, but if it simultaneously touches two wires at different electric potentials — bye-bye, birdie.

In the 1960s and ’70s, physicists extended this idea, finding other hidden symmetries associated with conservation laws to develop the standard model of particle physics.

“There’s this conceptual link that — once you realize it — you have a hammer and you go in search of nails to use it on,” Wilczek says. Anywhere they found a conservation law, physicists looked for a symmetry, and vice versa. The standard model, which Wilczek shared a 2004 Nobel Prize for his role in developing, explains a plethora of particles and their interactions. It is now considered by many physicists to be one of the most successful scientific theories ever, in terms of its ability to precisely predict the results of experiments.

At the Large Hadron Collider, at CERN in Geneva, physicists are still searching for new particles predicted using Noether’s insights. A hypothetical hidden symmetry, dubbed supersymmetry because it proposes another level of symmetry in particle physics, posits that each known particle has an elusive heavier partner.

So far, no such particles have been found, despite high hopes for their detection (SN: 10/1/16, p. 12). Some physicists are beginning to ask if supersymmetry is correct. Perhaps symmetry can only take physicists so far.

That notion is leaving some physicists in a bit of a lurch: “If that’s not going to be your guiding motto all the time — that more symmetry is better — then what will be your guiding motto?” asks mathematical physicist John Baez of the University of California, Riverside.

Holograms get symmetric

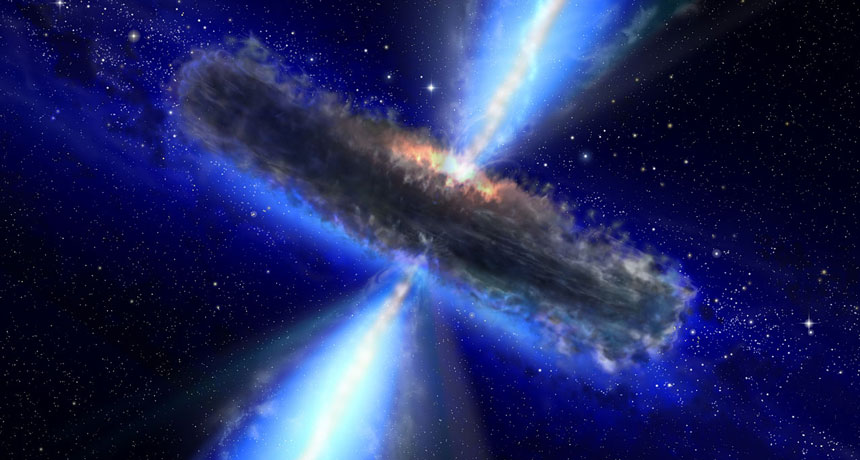

Despite such disappointments, symmetry maintains its luster in physics at large. Noether’s theorems are essential tools for developing potential theories of quantum gravity, which would unite two disparate theories: general relativity and quantum mechanics. Noether’s work helps scientists understand what kinds of symmetries can appear in such a unified theory.

One candidate relies on a proposed connection between two types of complementary theories: A quantum theory of particles on a two-dimensional surface without gravity can act as a hologram for a three-dimensional theory of quantum gravity in curved spacetime. That means the information contained in the 3-D universe can be imprinted on a surrounding 2-D surface (SN: 10/17/15, p. 28).

Picture a soda can with a label that describes the size and location of each bubble inside. The label catalogs how those bubbles merge and pop. A curious researcher could use the behavior of the can’s surface to understand goings-on inside the can, for example, calculating what might happen upon shaking it. For physicists, understanding a simpler, 2-D theory can help them comprehend a more complicated mess — namely, quantum gravity — going on inside. (The theory of quantum gravity for which this holographic principle holds is string theory, in which particles are described by wiggling strings.)

“Noether’s theorem is a very important part of that story,” says theoretical physicist Daniel Harlow of MIT. Symmetries in the 2-D quantum theory show up in the 3-D quantum gravity theory in a different context. In a satisfying twist, Noether’s first and second theorems become linked: Noether’s first theorem in the 2-D picture makes the same statement as Noether’s second theorem in 3-D. It’s like taking two sentences, one in Japanese and one in English, and realizing upon translating them that both say the same thing in different ways.

New directions for Noether

Everyday physics relies on Noether’s theorem as well. The conservation laws it implies help to explain waves on the surface of the ocean and air flowing over an airplane wing.

Simulating such systems helps scientists make predictions — about weather patterns, vibrations of bridges or the effects of a nuclear blast, for example. Noether’s theorem doesn’t automatically apply in computer simulations, which simplify the world by slicing it up into small chunks of space and time. So programmers have to manually add in conservation laws for energy and momentum.

“They throw away all of the physics, and then they have to try and force it all back in somehow,” says mathematician Elizabeth Mansfield of the University of Kent in England. But Mansfield has found new ways to make Noether’s theorem apply in simulations. She and colleagues have simulated a person beating a drum inside a simplified Stonehenge, determining how sound waves would wrap around the stone — while automatically conserving energy. Mansfield says her method, which she will present in September in London at a Noether celebration, could eventually be used to create simulations that behave more like the real world.

In addition to Noether’s importance in physics, in mathematics her ideas are so prominent that her name has become an adjective. References to Noetherian rings, Noetherian groups and Noetherian modules are sprinkled throughout current mathematical literature.

Noether’s work “should have been a wake-up call to society that women could do mathematics,” Gregory says. Eventually, society did awaken. In a 2015 lecture she gave about Noether at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada, Gregory showed a slide of herself with five female colleagues, then at the center for particle theory at Durham University. While women in science still face challenges, no one in the group had to struggle to get paid for her work. “That is Noether’s legacy, and I honestly think she would have been really jazzed,” Gregory says. “I think this would have been her real … vindication.”